Three Forgotten Democratic Tools from History November 24, 2014

Author: Beach Combing | in : Ancient, Medieval , trackbackWestern democracies run on a fairly limited model with relatively little variety from country to country. There follow three features that have disappeared from our contemporary democracies but that worked (and worked well) in the three most significant strands of historical democracies: ancient Greece, the medieval Italian communes and Viking ‘controlled anarchy’.

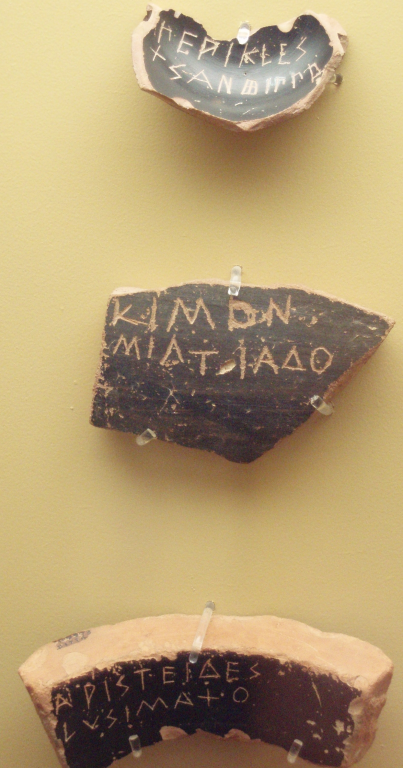

Ostracisim

Ancient Athens had ostracism built into its constitution. Each year the Athenians would vote on whether they wanted to ostracise. If they decided to do so, then all voting citizens would write the name of a fellow Athenian on a sherd of pot (many of which survive) and if any citizen reached 6000 ‘votes’ (no easy matter), then he would be ordered to leave Athens for ten years. His property would not be touched, his assets were left in place, but if he attempted to return to the city he would be killed. The system proved effective at getting rid of ‘big heads’ men who so dominated the body politic that they threatened Athenian democracy (or were perceived to do so). It also meant that all politicians in Athens had to court not only their own side but also other groups: it was fine to irritate the conservatives, say, but you were finished if they hated you. Ostracicsm interestingly was associated not so much with factions fighting factions but with normal Athenians punishing arrogant elite members. Could this work in a modern democracy? It would be a way of getting rid of particularly divisive figures: Hilary Clinton or Sarah Palin, for example, would have been hurried into exile a long time ago in the US. But what happens if Winston Churchill was ostracised in the middle of the 1930s at the height of his unpopularity? Athens, on occasion did reverse ostracism…

Lottery

The comune of medieval Florence ran a semi-democractic system where only guild members were full citizens. However, guild members rarely voted. The Florentine Republic was essentially run by committee and though there was voting in the committees and occasionally in assemblies (typically to operate vetoes) committee members, the fundamental unit in Florentine government were not elected. How then were they chosen? A pool of potential office holders was established through a scrutiny committee and then the office holders, who held office for short periods of two or three months, had their names drawn from a hat. The closest parallel with the modern world is the Anglo-Saxon jury system where members are picked at random and then, in a reverse of the Florentine system, filtered after being placed in the jury pool: in Florence citizens were filtered, placed in a potential officer pool and then chosen. The system was eventually manipulated by the Medici – the bastards – but worked well for perhaps two hundred years prior to the mid fifteenth century. How could a lottery system be applied today? G.K.Chesterton had some fun with this in the Napoleon of Notting Hill, where a fool becomes King of England after being chosen by a raffle. But there are other possibilities: imagine ten percent of representatives in a parliament being chosen by lottery from a pool of citizens aged 20 to 70 without criminal records. You would have a truly independent faction in national legislatures, ready to fight for country rather than party interests.

Extra-territoriality

In medieval Iceland there were a series of gothi or local strongmen. These figures were, in some respects, the equivalents of aristocratic lords in other European societies. However, there was an important difference. Icelanders did not just follow the local gothi. They chose which gothi to follow within their own general area. This choice mattered. It would define who you would fight in the case of a feud, but it also defined other choices that you would make including justice and local welfare. If the gothi were essentially petty state rulers, then we have a situation where Icelanders could decide what state to belong to: one medievalist has even gone so far as to say that every Icelander was a king, a privilege that we living in modern democracies would not recognise. There have been some rather careless comparisons between anarcho-capitalism and medieval Icelandic democracy. But the key point that you have individuals not just voting but choosing their own form of government (from a limited ballot paper admittedly) does recall some modern anarchist thinking where individuals can opt in and out of state control at will, creating their own micro-states, for example the impractical but profoundly exciting writing of Robert Nozick (obit 2002).

Other forgotten democractic tools: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com