Why Do We Forget Soviet Murder? October 14, 2015

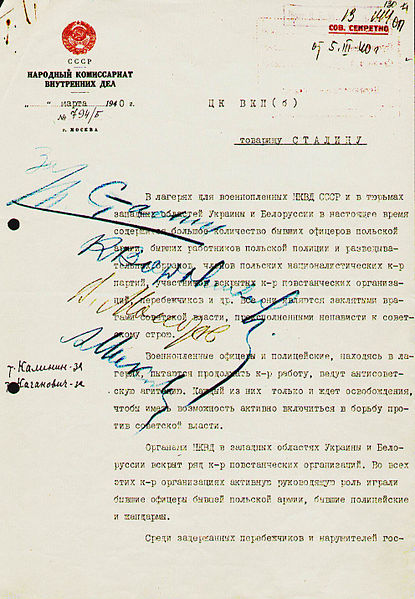

Author: Beach Combing | in : Contemporary , trackbackBetween 1917 when Lenin declared the revolution to 1956 and the invasion of Hungary Soviet massacres of innocents or opponents were frequent, massive and only seriously contested in the West by the small national Communist parties. Yet one of the extraordinary things about these bloody outbursts is that they have been forgotten by all but those most intimately concerned with them. For instance, in 1932 and 1933 Stalin murdered (by a centrally planned famine) between three and seven million Ukrainians: this stands at the very centre of Ukrainian identity today, but is practically unknown outside Ukraine and its always energetic diaspora. Another example, at Katyn in the spring of 1940 the Soviet security apparatus killed about 22,000 Poles, including much of the Polish officer’s corp, and Poland’s cultural and scientific leadership (the kill document signed by the politburo heads this post). Again in Poland, Katyn is the subject of films, of documentaries and of books: say, Katyn in much of the rest of Europe (at least in the west) and you will be thought to be coughing up flem. It would be bad enough if we were simply unable to remember Soviet atrocities. But we actually seem to be getting worse. In the Cold War there was at least a steady leak of such stories (funded by western liberals and western intelligence agencies) to discredit the Soviet Union. The west was always careful to keep the tone of these debates down: because the whole point of the Cold War was that it was necessary to win quietly. But if someone seriously stood up on French television (perhaps a dinosaur from the PCF) and began to muse about Stalin there would have been a queue of socialists and republicans ready to shoot the speaker down. Now the Cold War is gone there is not even that steady flow of information into the western bloodstream.

Why do we forget so easily: drbeachcombing AT yahoo DOT com

The fascinating comparison is with the Holocaust which is at the very centre of western literature, western film and western memory. Perhaps every decade between the 1940s and today (albeit from a terribly low level) has seen more and more intense attempts to remember what the Third Reich did to Jewish Europeans (with the possible exception of the last ten years?). Maybe in the end countries, like people, have simple memories and are not very good at remembering more than one thing. It is fascinating how when we recall the six million Jewish Europeans murdered by Hitler we concentrate overwhelmingly on the camps and above all the gas chambers: only half though of Hitler’s victims actually died in the camps, while hundreds of thousands were killed in trenches and fields in the east, the little known ‘outdoor killings’.

17 Oct 2015: Norm writes: I’ve known a few Ukrainians over the years, even a few who lived through Stalin’s years and trust me they were not shy about telling their story but I’ve never gone to a lecture put on by a survivor. We had a lecture here in my little township in Ohio from a Jewish person who survived Hitler just this past week, they are very common. The jewish people were spread across Europe, they were of many nationalities, they were us, not some people from somewhere on the map. Hence the difference in how we remember.

Nathaniel writes: The Germans are “us”. What they do reflects directly on “us” and “our” values. When Germany kills millions it calls “our” entire culture into question. The Russians aren’t “us”. They have a different culture that seems more like that of (say) China than like “ours”. When Russia or China kill millions, it’s horrible but it does not reflect on “us” in the same way (well, except as members of the same human species…)

Southern Man: You’ve got this back to front, old chap. We forget everything. The holocaust is special because we associate it with ourselves, our culture, our people, our evil (as indeed it was)

Bruce T writes: The simple reason Katyn wasn’t confirmed in the States for what it was, was by and large the result of Yurshenko’s triple cross. Intelligence services in the West were loathe to get caught with their pants down after Vitaly’s Big Adventure. Until the Eastern Bloc fell and the documents from the other side were officially out for the world to see re; Katyn, nothing was going to be said. Our side still had what they considered a few good sources who upheld the theory of Katyn being a German operation. They wanted to play it close to the vest. I can tell you w/o violating anything that I saw a CIA whitepaper as an undergrad in the late 70’s that laid Katyn clearly at the feet of the Soviets. Internal politics and ass covering kept it under wraps for another decade plus.

30 Oct 2015: Stephen D writes ‘You asked (Oct 14th) why Hitler’s crimes get so much attention, while those of Lenin, Stalin, Mao etc are left relatively obscure. In general I suspect simple explanations, but in this case there is an obvious one. The Nazis committed acts of appalling barbarism in the pursuit of two goals: maximum power & expansion for Germany, and the elimination of those whom they saw as racially undesirable – Jews, Slavs, Gypsies. Very few people outside Germany ever supported the first, and in modern times very few in Western Europe or North America supported the second. Therefore, almost everybody is happy to condemn the Nazis wholeheartedly. The Soviets and their allies committed acts of appalling barbarism in the pursuit of different goals: the overthrow of capitalism, the destruction of the previous social order, the creation of a just and socialist/communist society. Many people in Western Europe or North America have supported, and some still do support, such goals. Therefore, these supporters are reluctant to make much effort to condemn Soviet murders: some because they fear that if it is emphasized that the path to desirable socialism can lead to dreadful crimes, then people may be reluctant to embrace socialism; and some because they believe that Soviet crimes would have been justified if they had led to communism; and others because they in their hearts want a bloody revolution, extermination of the class enemies, dictatorship of the proletariat (or at least of the revolutionary party), and so forth. I used to think that the last two types were a dwindling minority, but nowadays I fear not.’